Does it invade my privacy? Then I don’t want it.

Published on 26 07 2023DRIVERS OF ACCEPTANCE FOR RADICAL INNOVATIONS

Article by Lisette Kruizinga – de Vries

innovations are a great source of growth

Innovation and more specifically, new product innovation is considered to be one of the biggest sources of growth (e.g., DVJ´s own Brand Growth studies). And successful companies believe in this even more.

However, what do we mean exactly by innovation? McKinsey & Company defines it as follows: “Innovation is the systematic practice of developing and marketing breakthrough products and services for adoption by customers.” We have asked marketing managers the same, and they came back with insightful answers like: “Innovation is constantly looking at how things can be made differently, better and more efficient” and “For me, innovation is something that fuels relevance for the consumer. It doesn’t have to be overwhelming; it can be something small as well.” So, innovations can be either small or big, should be something different than what was already there, and need to have relevance for consumers. Because many companies agree that innovation is a driver of growth, many companies decide to introduce new consumer goods, with approximately 30,000 new products being introduced each year in the United States alone (NielsenIQ, 2019). This is the equivalent of a whole supermarket!

Incremental versus radical innovations

Most of these consumer good introductions can be considered incremental innovations. These are innovations that are closely related to products or services that consumers already know and use. In that sense, these innovations are not very new or different and have little risks involved for consumers.

On the other hand, innovations might also be more radical and extreme, some may be more intrusive and some even disruptive to the industry. Disruptive innovations change the whole industry, for instance, Spotify shook up the music industry (Christensen, Raynor & McDonald, 2015). It might be quite difficult for firms to sell more radical innovations, hence the key is to clearly highlight the benefits of the innovation and its differentiating aspects as well as clarify why it is better than the product consumers are currently using.

Importantly, research has also shown that the long-term effect of innovation on a firm’s stock market value is positive and is larger for radical than incremental innovations (e.g., Sorescu & Spanjol, 2008), making it interesting for firms to invest in radical innovations.

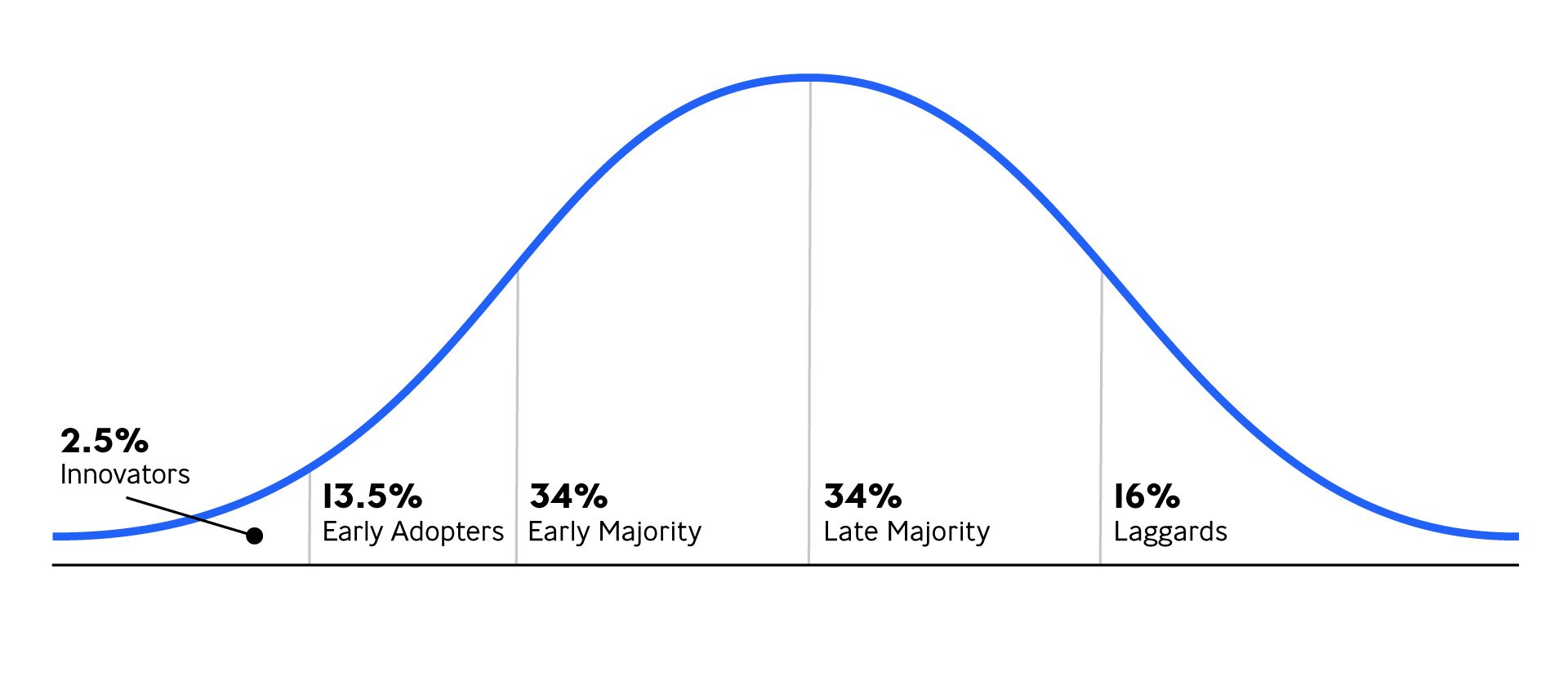

In this sense, it is also important to mention that there are differences between consumers in their tendency to adopt innovations or generally new things (Rogers, 2003). Some people are always ahead of things and want to be the first ones to have something new, whom we call the innovators. Then, there are the early adopters, followed by the early and late majority (Figure 1). And finally, the last group of people who will eventually adopt are the laggards. Research has shown that consumer innovativeness affects their likelihood of trying new products (e.g., Steenkamp & Gielens, 2003).

So, the extent to which an innovation will be successful is determined firstly by the innovation itself – i.e., how clearly are the benefits of the innovation described, how good is the innovation, how is it perceived by the target group, and so on – and secondly on consumers and their innovativeness. So, what are the success rates of all new consumer products?

Figure 1: Diffusion of innovation model by Rogers (2003)

Most innovations fail – but why?

We know that many innovations fail, and especially new introductions in FMCG, whose failure rates can be up to about 75% within one year (O’Reilly, 2014) ), whereas the average failure is about 50%. But what are the reasons for failure? Firstly, most consumers buy what they always have been buying, and simply do not look at or consider other products. Another crucial reason why product introductions fail is that there has not been done any market research on the new product. Another reason for failure is that most of the budget is used to create the product, and only little is left for launching or marketing. Of course, there are many other reasons behind the low success rate however, many would be tackled if marketing research had been done. Think about the following that could have been prevented: ‘The product’s key selling points or advantages are not clearly articulated; consumers have not tested it; the target audience is unclear or it is unclear which consumers would like the new product; the ad campaign has not been tested and does not work’, etc. (Schneider & Hall, 2011). Although not everything can be solved by testing before launch, some of the very crucial points can.

Winners test more often than non-winners

What we found in our Brand Growth study is that companies that are growing and more successful, do test innovations more often than unsuccessful companies. What we also saw is that winners simply have much more budget and time than losers. Therefore, testing innovations before launch can help make your product introduction a success. At DVJ Insights, we developed a concept test that tackled questions like: What is the strength of your new product? Which pros should be especially mentioned? What is the right way of introduction and what should the communication focus on? How can I increase acceptance?

As one might expect, we frequently test incremental innovations, such as a new type of yoghurt, meat snacks (which are very popular in the UK), or wall paint. We have tested a lot of these innovations, and generally know how they score on the metrics used in our concept test and how these metrics relate to each other. We have built up an extensive benchmark, and when testing an innovation we have a clear indication of whether it will be a successful one or not.

As the majority of innovations are incremental, we have limited information on how radical or intrusive innovations are evaluated and valued, which could be extremely useful for firms because these innovations involve greater risks. We expect that evaluations and acceptance of these more radical, extreme and out-of-your-comfort-zone innovations might differ from incremental innovations.

To begin with, it is expected that they will score significantly higher on the evaluation of new and different and that acceptance rates will be lower. Moreover, it is expected to find differences in evaluation and acceptance behaviour between people who differ in their innovation proneness (e.g., innovators vs. laggards). Therefore, we decided to test more radical innovations in an internal study to gain more insights into responses to these types of innovations.

Our research set-up

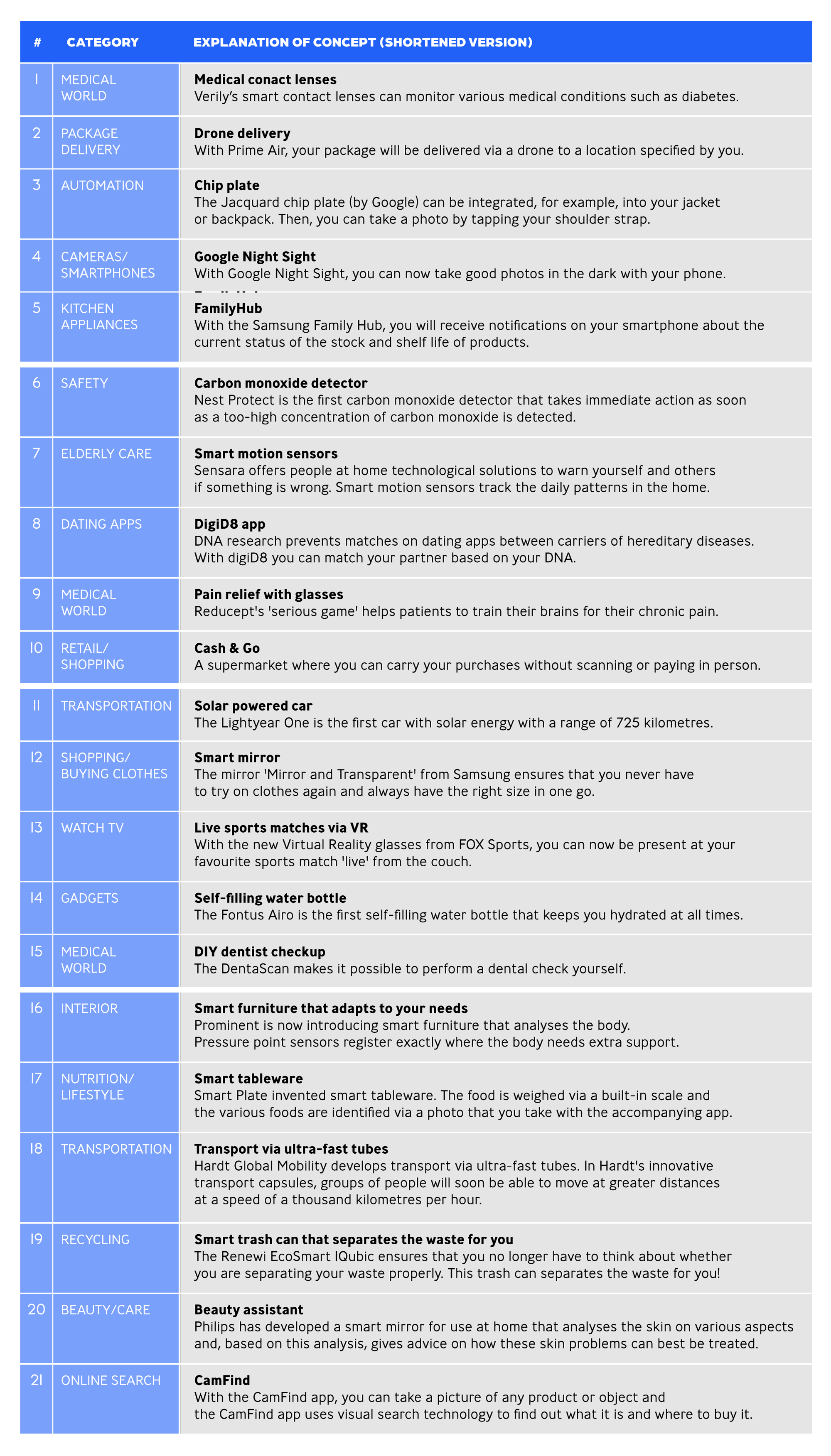

For this study, we have tested 21 innovations that are more radical in our own concept test (see Table 1 for a full description of the concepts).

Table 1: Overview of all tested innovations

The innovations come from a variety of fields, including medicine, automation, cameras, and safety. Each respondent got five concepts to test, and we have about 100 respondents per concept. We tested these concepts in the Netherlands among a representative set of respondents. The set-up of the study is holistic and contains different elements and techniques, such as overall appreciation of the concept including reasons why they appreciate it or not, the level of acceptance, and evaluation of the concept and it concludes with background questions of the respondent, such as education level.

In the background section of the survey, we also asked to what extent they are open to new ideas and the likelihood that they would adopt innovations (as inspired by Rogers). We could later use these questions to classify respondents into one of the categories as defined by Rogers.

We also classify the concepts based on their level of radicalness, whether they are privacy intrusive, personal and how often people would generally use them. The coding has been done by two people, independently of each other. Any inconsistencies in the coding were resolved in a discussion and cross-checked with a third person.

First insights – HOT OR NOT radical innovations

First of all, do our results show that radical innovations are indeed perceived differently by respondents? When comparing the scores on the tested innovations with our concept benchmark, we do see that they are indeed perceived differently. First of all, we find that acceptance scores of these concepts are on average 34%, which is significantly lower than our benchmark score (42%) which contains mainly incremental innovation concepts.

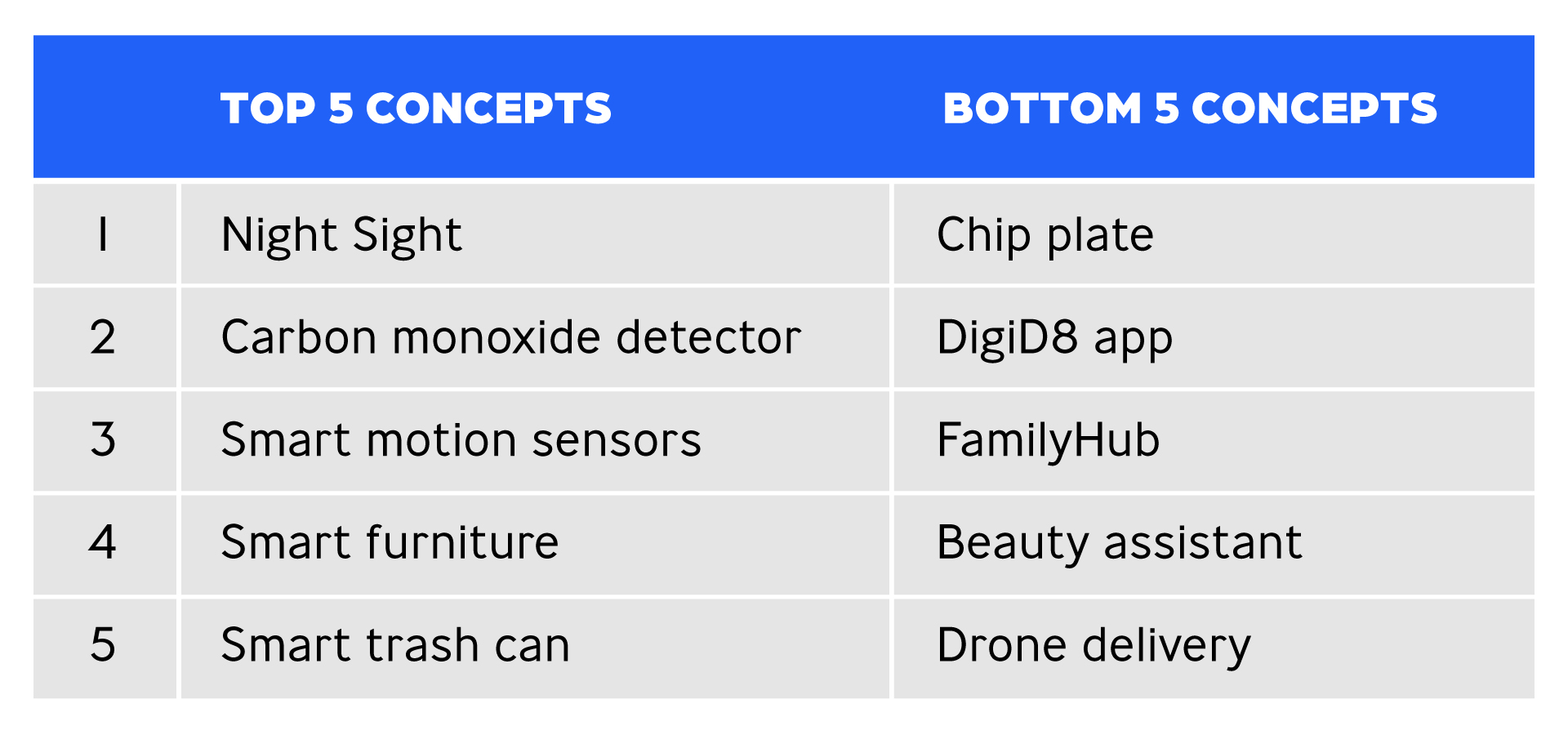

Also, the overall evaluation of the concept (44%) scores significantly lower than our benchmark (62%). We do observe also significant differences between the concepts. The difference in the score for the overall evaluation of the concept is almost 47% points between the lowest and highest scoring concept. When looking at the top 5 concepts (see Table 2), we see which ones are evaluated highly. Interestingly, the hot concepts are almost all related to smart homes, except for the Night Sight.

Table 2: Top 5 and bottom 5 concepts based on the overall evaluation

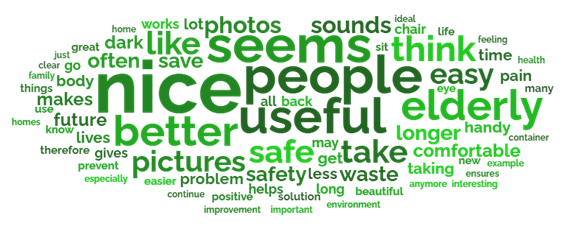

And when taking a closer look at the reasons why people evaluate those as positive (see Figure 2; where we exclude the words good idea as it is not providing much insight), we see interesting patterns emerge. More specifically, safe is an often-used word, that is relevant for both the carbon monoxide detector as well as the smart motion sensors. Other words that are often mentioned are nice, useful and easy; people do see the added value of the concepts and believe that they can make their lives more easy and comfortable and can maybe even save lives (in the case of the carbon monoxide detector and the smart motion sensors).

Figure 2: Positive points about the Top 5 concepts

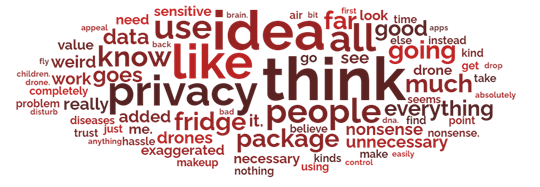

Looking at the bottom 5 concepts (see Table 2), it seems that they are too intrusive as they are very personal and take away control over the user. Especially regarding the DigiD8 app, people believe this goes too far and is an invasion of their privacy. The latter is something that is mentioned for all the bottom 5 concepts. Moreover, words that are also often mentioned are exaggerated, nonsense, unnecessary, no added value, redundant, etc. Hence, people do not see the benefits of these new product ideas and become defensive and don’t trust them. See Figure 3 for an overview of the most often mentioned words.

Figure 3: Negative points about the Bottom 5 concepts

Evaluation of radical innovations scores lower than incremental innovations

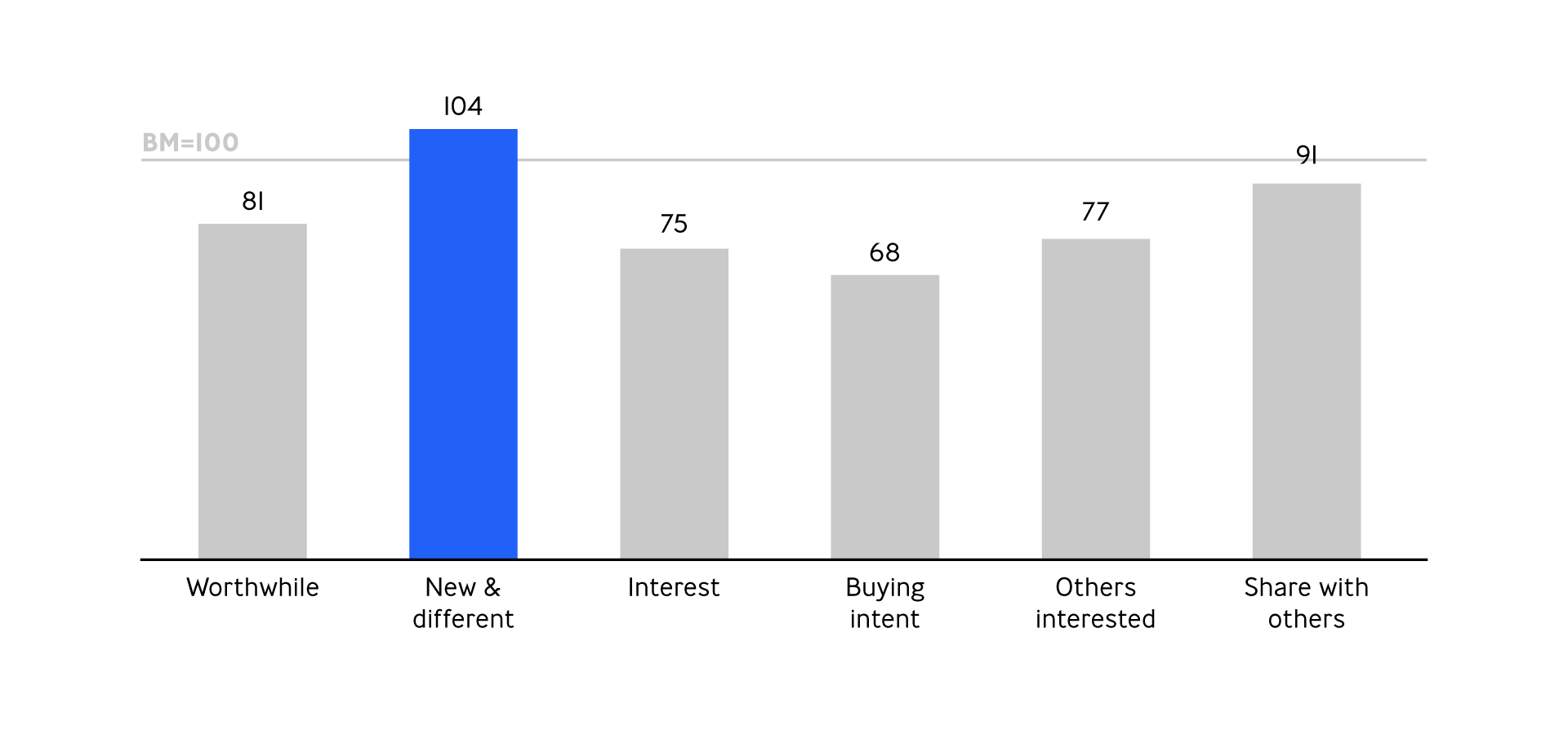

When diving a bit deeper into the different statements of evaluating the concepts, we find that on average, all concepts are evaluated significantly lower on almost all accepter-rejecter statements. The index scores can be found in Figure 4 and they are indexed so that the benchmark score equals 100. More specifically, the scores are computed by dividing the average score for the radical innovations by the benchmark score and then multiplying by 100.

That makes it easily observable that the average index score for new & different is higher than 100, meaning the tested concepts score higher on this element than the benchmark. This is not surprising given the more extreme nature of the concepts tested. However, scores on worthwhile, interest, buying intent, others interested and share with others score significantly below 100, thus indicating that our more radical concepts score lower on these statements than the incremental innovations we generally test. On average, the concepts score especially low on buying intent. Sharing with others scores the highest, after new & different, which might be explained by the fact that the concepts are perceived as new and different and thus interesting to share.

Figure 4: Index scores for accepter–rejecter statements

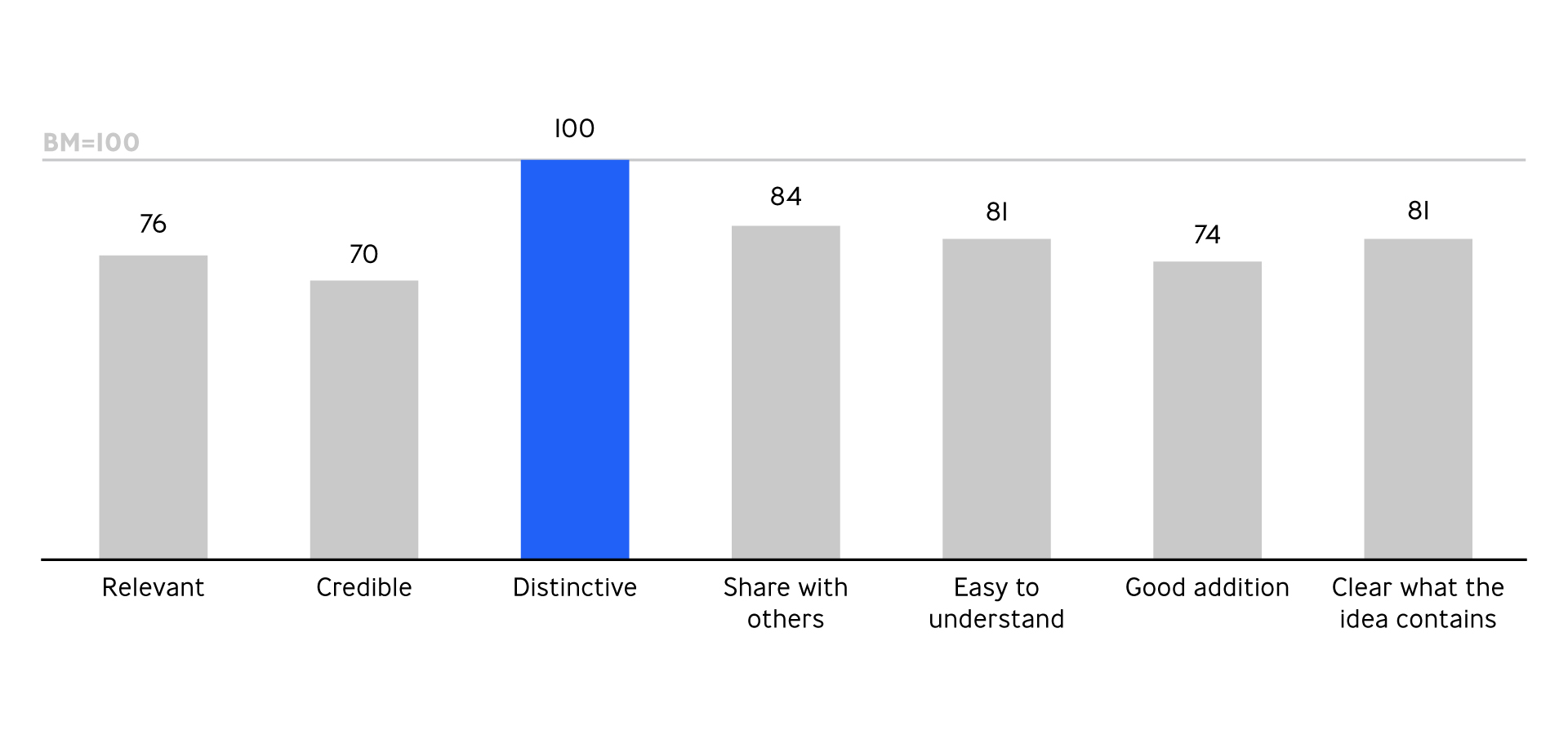

Figure 5 represents the index scores for the evaluation statements. What we observe here is a similar pattern as for accepter-rejecter statements. The tested concepts score lowest on credibility, a good addition to current offerings and relevancy. Understanding and sharing with others score a bit higher, but still below the benchmark, and distinctiveness scores on the benchmark. This is an interesting finding as it indicates that most people seem to like more radical innovations less than incremental innovations. This is interesting, although not that surprising as we know that people generally buy and prefer what they always buy and know.

Figure 5: Index scores for evaluation statements

Differences between people – innovators versus laggards

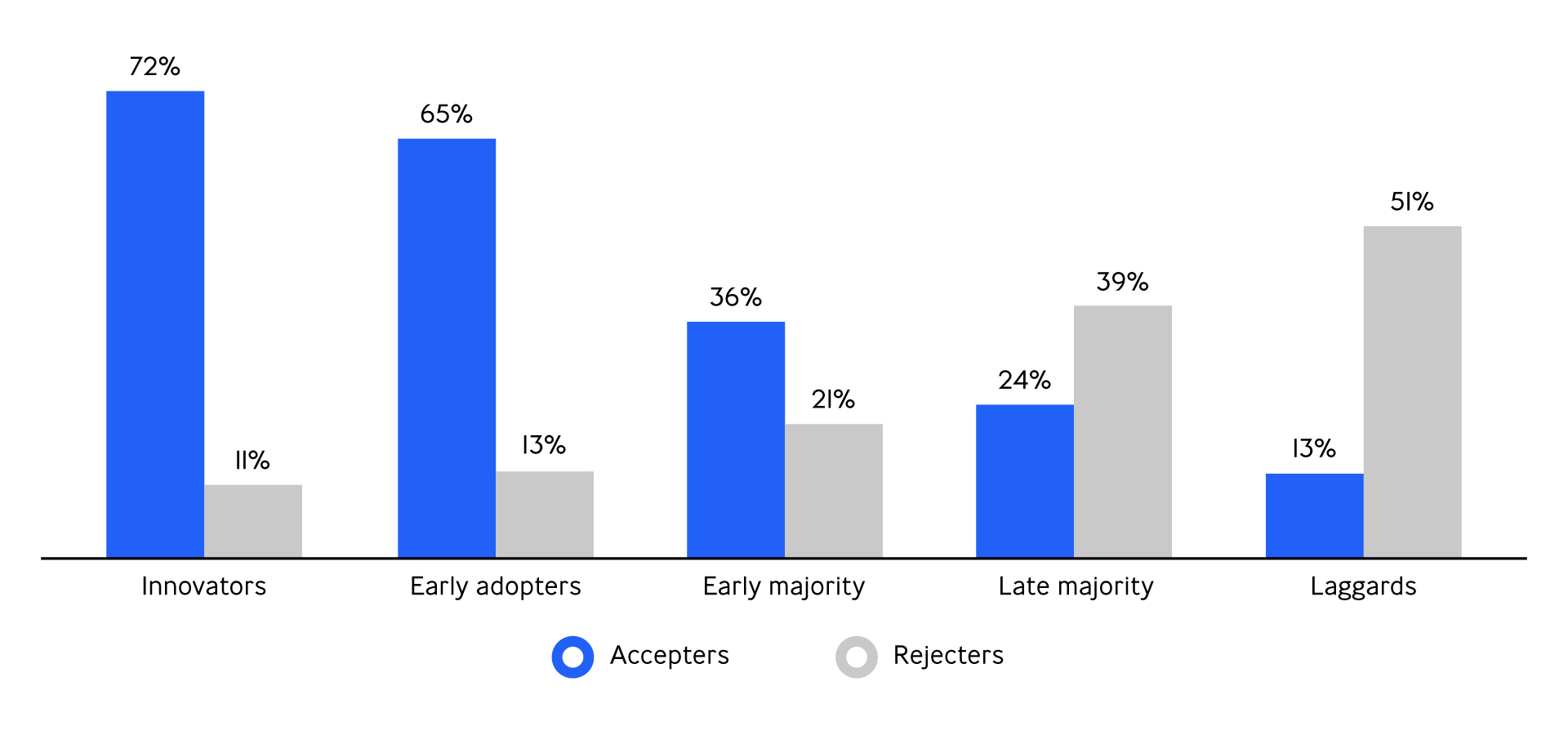

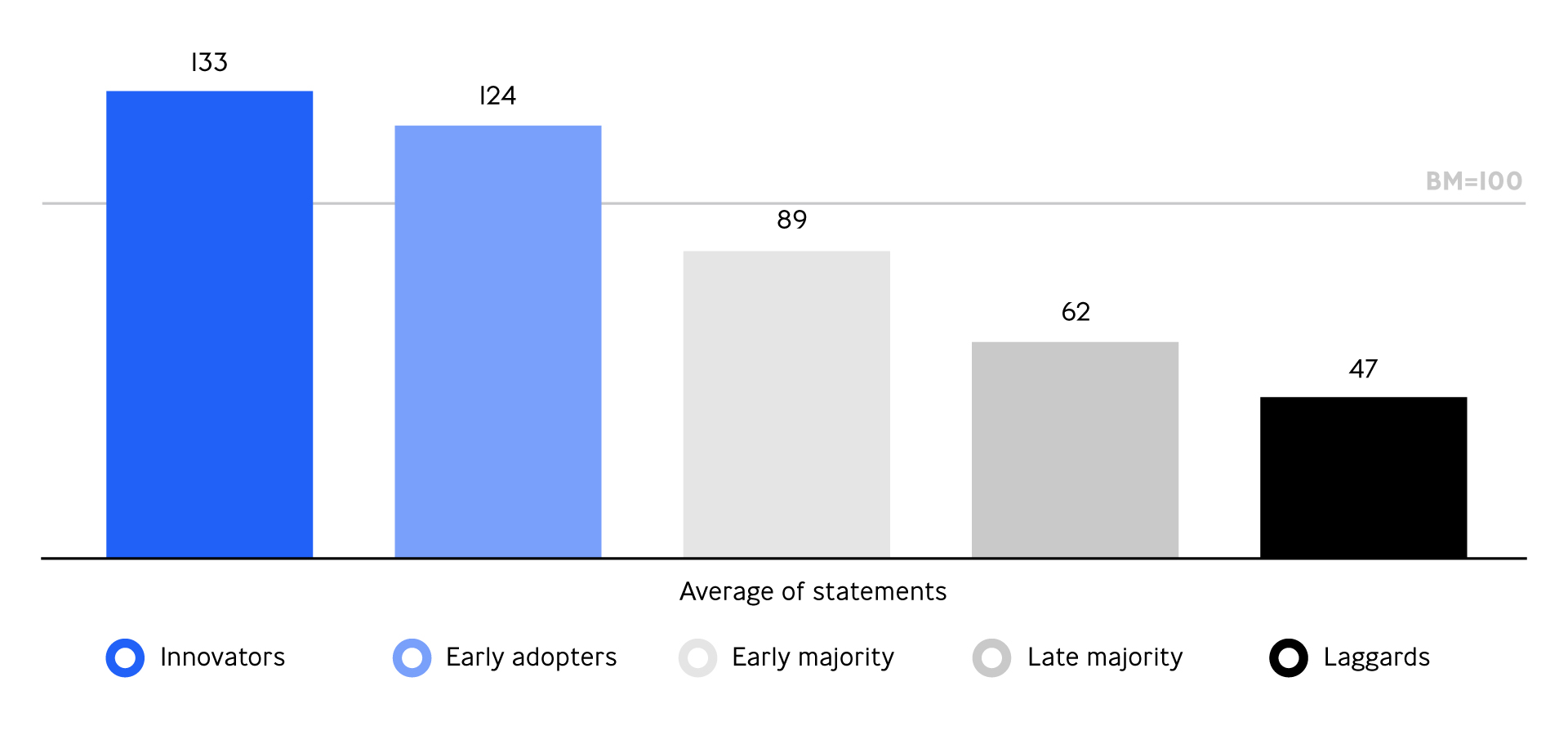

However, there are differences between people, and especially when looking at people from the classification Rogers made. As mentioned, we added a few questions that indicate respondents’ innovativeness and their openness to new ideas. By using these questions, we were able to divide respondents into the five groups as identified by Rogers, namely, the innovators, the early adopters, the early majority, the late majority, and the laggards.

Figure 6: Acceptance and rejecter scores for Rogers groups

Linking the Rogers classification of respondents to our accepters, potentials and rejecters of the different concepts indicates that innovators and early adopters are much more often accepters of these concepts, whereas the late majority and laggards are much more often rejecters (see Figure 6).

Additionally, examining the evaluation of the concepts for these different groups also indicates that innovators and early adopters are much more positive on average than the other groups, especially compared to the late majority and laggards (see Figure 7).

Figure 7: Average index scores for accepter-rejecter and evaluation statements for Rogers groups

What elements determine acceptance?

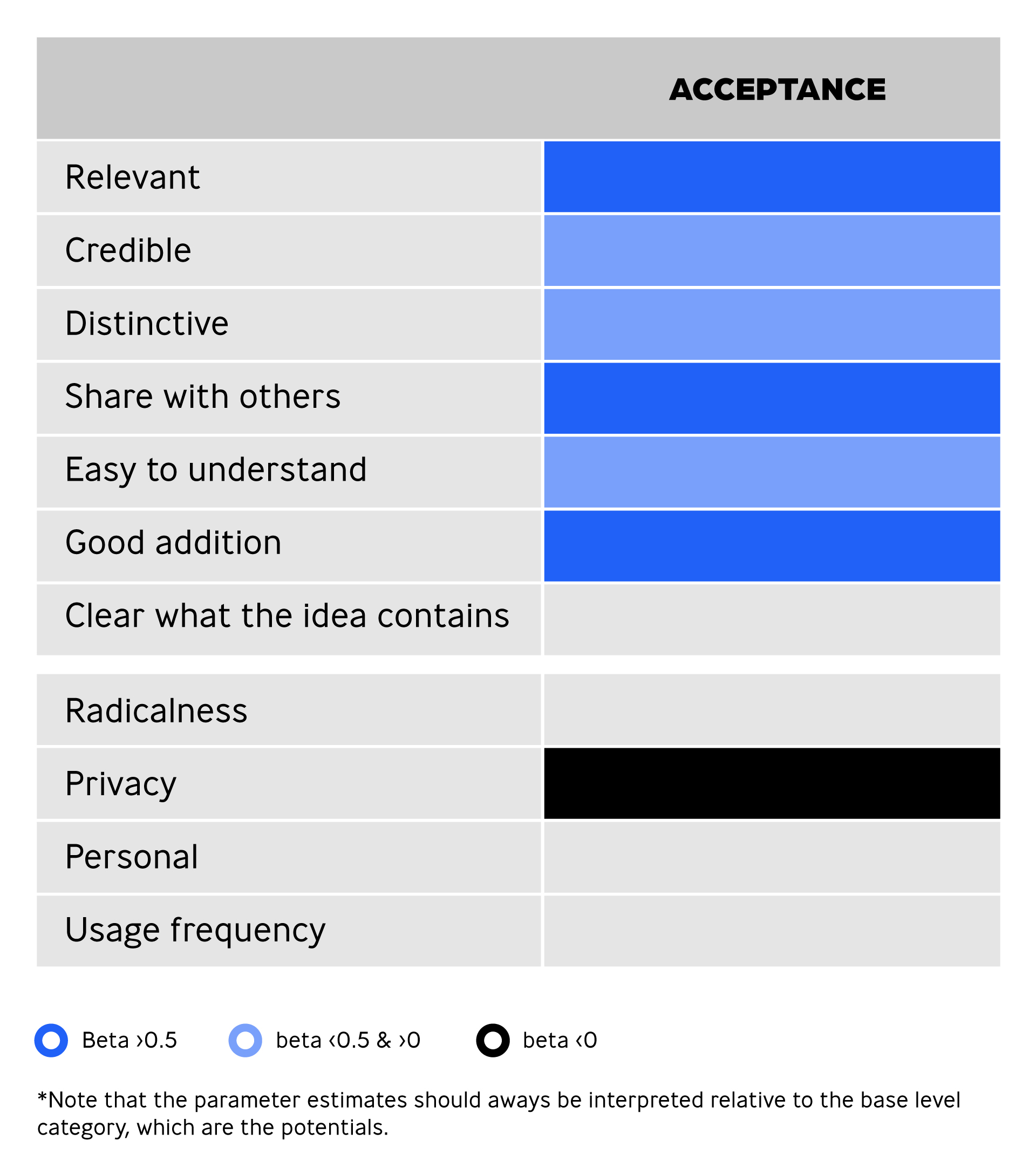

Finally, after seeing some descriptive findings, we also want to formally test which elements determine acceptance versus rejection. For this, we estimate a multinomial logit (MNL) model to be able to estimate the determinants of acceptance. More specifically, we estimate a model with the dependent variable whether someone is an accepter, rejecter or potential (whereby potentials is the base category). We include the evaluation statements (such as relevancy, credibility, etc.) and the classification of the concepts, namely the extent to which they are considered radical, privacy intrusive, personal, and usage frequency as independent variables.

Table 3: MNL model results for acceptance*

In Table 3 the model results for acceptance are reported. It was found that sharing with others, a good addition to current offerings, and relevancy have the largest positive effects on the acceptance rate (see Table 3). This is an interesting finding as we found that radical innovations score lowest on relevancy and a good addition. So, if they can score well on those variables, this has a great impact on acceptance levels. Additionally, highly privacy-intrusive concepts have lower chances of being accepted. This is something that we also saw in the open answers and now we can confirm it is indeed affecting acceptance.

Finally, we also estimated the model by including an interaction effect between privacy and personal, to examine whether this might have an even more negative effect but the interaction effect appeared to have no significant impact on the level of acceptance.

Conclusion

This article discussed the case of radical innovations and what is driving their acceptance. First of all, we know that innovation is an important source of growth and that growing companies generally spend more time and more money on innovations. They also test new concepts more often. Since we, at DVJ Insights, most often test incremental innovations, we conducted an internal study on more radical and intrusive innovations. And we found some interesting things:

- More radical concepts are evaluated less positively on average than our benchmark, which consists primarily of incremental concepts.

- We do see large differences between the different radical innovations concerning evaluation and acceptance levels.

- We also observe large differences among people – Those who are more prone to innovations and new things, evaluate radical concepts more positively and are more likely to accept them than people who are not that open to innovations.

- Finally, we find that relevant innovations, a good addition to what is already available, have higher acceptance levels. However, if a concept is too invasive in someone’s privacy, people are less likely to accept it.

Managers can use these findings to improve concepts or innovations. It is critical to understand how people evaluate your concept prior to product launch to enhance understanding, relevancy, evaluation and the added value of the concept. These elements appear to be crucial for new product acceptance.

references

Christensen, C.M., Raynor, M. & McDonald R. (2015). What is disruptive innovation? Harvard Business Review, December, 1-11.

McKinsey & Company (2022). What is innovation? August 17, 2022. Accessed via: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/mckinsey-explainers/what-is-innovation#/

Nielsen IQ (2019). Bursting with new products, there’s never been a better time for breakthrough innovation. Accessed via: https://nielseniq.com/global/en/insights/analysis/2019/bursting with-new-products-there-never-been-a-better-time-for-breakthrough-innovation/

O’Reilly, L. (2014). 3 in 4 FMCG launches fail within a year. MarketingWeek, 9 September 2014. Accessed via: https://www.marketingweek.com/3-in-4-fmcg-launches-fail-within-a-year/

Rogers, E.M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). New York: Free Press.

Schneider & Hall (2011). Why most product launches fail. Harvard Business Review, April.

Sorescu, A.B. & Spanjol, J. (2008). Innovation’s effect on firm value and risk: Insights from consumer packaged goods. Journal of Marketing, 72(March), 114-132.

Steenkamp, J.B.E.M. & Gielens, K. (2003). Consumer and market drivers of the trial probability of new consumer packaged goods. Journal of Consumer Research, 30(3), 368-384.