UNDERSTANDING THE IMPACT OF UTILITARIAN AND HEDONIC PRODUCT VALUE ON BUYING INTENTIONS OF INNOVATIONS, WITH THE MEDIATION EFFECT OF ACCEPTANCE

by Despoina Vardaki & Lisette Kruizinga-de Vries

Nowadays, hundreds of thousands of new products are introduced into the market. But how can a customer notice a new product when a typical grocery store carries on average 30,000 different products (Rooks, 2022)? For example, how does someone decide which laundry detergent to buy when there are 18 types of it, or how to choose among all the types of tea, chips, cookies or yoghurt? Due to this huge supply of products, people prefer to buy the same items again and again. For example, American families typically buy the same 150 products that account for up to 85% of their household needs (Schneider & Hall, 2021). That leaves new products and brands fighting to get a spot in the remaining 15%. Therefore, it is crucial for businesses to understand how willing customers are to buy a new product. In order to increase an innovation’s chances of being accepted and adopted, it is essential to understand why consumers want to purchase a new product. This study looks at the value that consumers derive from the product. Hedonistic or utilitarian?

Before customers adopt a new product, they have to evaluate the attributes of a new product subjectively to understand if it fits their needs while also being influenced by their network (Rogers, 2003). All this influence and information that they have to process is affecting their buying behaviour, sometimes even by suppressing it (Shiu, 2021).

Companies develop more and more products in order to satisfy their customers’ needs but almost half of them fail (Castellion & Markham, 2013). If the failure is constant, this can be critical for the survival of the organisation since it can hurt its legitimacy (Rura-Polley, 2001). Thus, it is of great importance for companies to understand customers´ willingness to purchase a new product compared to thousands of others. In this study, it is examined what value customers extract from the product. Hedonic or utilitarian? Understanding why customers want to buy a new product may be critical in improving an innovation’s chances of being accepted and adopted.

Joy or functionality – how do they influence buying behaviour?

The value created by purchasing and using a product is a factor that influences a customer’s purchasing behaviour. In this research, we consider two types of product value – the hedonic and the utilitarian value. Specifically, these values include the reasons why a customer opts to buy innovation. The utilitarian value of an innovation is determined by its usefulness, whereas the hedonic value is determined by the satisfaction it provides while in use (Bettiga et al., 2020). Hedonic items are joyful, entertaining, intriguing, wonderful, and exciting in contrast to utilitarian products, which are practical, useful, functional, essential, and effective (Dhar & Wertenbroch, 2000; Voss et al., 2003).

Not only are hedonic items different from utilitarian ones but also the emotional responses that come from their use differ. Compared to utilitarian items, hedonic products generate more intense emotional responses and sentiments from the user (Holbrook & Hirschman, 1982). According to research, hedonic products cause more arousal, enjoyment, and commitment (e.g., Kivetz & Simonson, 2002) than purely utilitarian ones.

In this research, it is expected that new utilitarian products will have higher buying intentions than hedonic ones. People might accept a hedonic product more, but due to the hedonic nature of the product they might feel quilt, especially when they buy it for themselves, hence they might not intend to buy it although they accept it, for example as a gift (Lu et al., 2016). In fact, the greater the expected guilt for consuming/using a product with hedonic value, the less likely consumers are to purchase it overall (Lu et al., 2016). Thus, products with utilitarian value might be more dominant in positively affecting buying intentions, which is reflected in hypothesis 1.

On the other hand, customers are more likely to recognise positive feelings caused by a hedonic rather than a utilitarian product, thanks to its attributes and use (Bettiga et al., 2020). Moreover, it is found that emotional responses towards the product drive decision-making with consistency in the ways that they affect product evaluation (e.g., Bettiga & Lamberti, 2017) and acceptance, which is measured by how people evaluate the new product. Thus, it is expected that the hedonic value of innovations will be more accepted, compared to utilitarian ones, since that positive cognitive feeling that comes through the hedonic value of a product, might be more easily reflected on its acceptance, leading to hypothesis 2.

Finally, as acceptance reflects that overall impression and attitude towards the product concept, acceptance is expected to positively affect buying intentions, which is reflected in hypothesis 3. It will be tested whether acceptance is mediating the relation between product value and buying intentions.

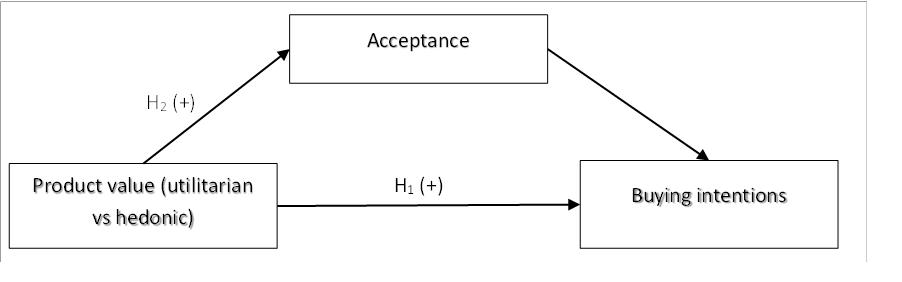

The expected relations are summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Conceptual model

HOW TO CODE HEDONIC AND UTILITARIAN VALUES?

The data used for this research contain concept testing results from 99 concepts, which were tested between 2017 and 2022 by DVJ Insights. It contains a good variety of concepts tested for products from various categories like paint, food, alcoholic drinks, banking, etc. For this research, we will only take into account the tests that are conducted in the Netherlands since there might be cultural differences in how customers behave in regards to buying new products (Singh, 2005).

DVJ’s concept test contains different elements, but the part that is relevant for this study is that respondents were shown a description of the product (i.e., after which they had to evaluate it. From these evaluation measures, we compute the acceptance which consists of different variables, and buying intentions which is a single variable.

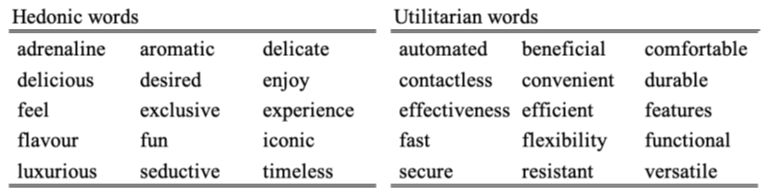

We used the product descriptions to extract the product value of each innovation. More specifically, the tokenisation of each word in each insight is used, always linking the words of each insight to the concept that they belong to. But firstly, it is necessary to remove the stop words. In order to do this procedure, different packages in R are used. In order to extract the utilitarian and the hedonic value of the words of the innovation’s insights, we use words associated with the utilitarian and the hedonic value. Two variables are created: one for the number of words with utilitarian value and another for the hedonic value of the insight. Specific keywords are derived from existing research (e.g., Voss et al., 2003), synonyms, and words found throughout the text of the insights that reflect either of the values. The utilitarian words are related to features of the innovations that reflect its functionality while the hedonic words are related to the aesthetics of the concept, with pleasure and experience. Table 1 includes some examples of words that were used to create these two variables.

Table 1: Examples of hedonic and utilitarian words

Findings

To gain insights into the different effects of product value and assess mediation effects, four different linear regression models are estimated. The results are shown below:

- One part of product value, the hedonic value, has a significant (p-value = .004) and positive (β = .03) impact on buying intentions, whereas utilitarian values have no significant relation with buying intentions. This means that one additional hedonic word offers 0.03 (3%) more buying intentions, contrary to hypothesis 1.

- The hedonic value is affecting acceptance significantly (p-value = .0002) and positively (β = .029). Moreover, the quadratic term of the hedonic value is affecting acceptance significantly (p-value = .002) and negative (β = -.001). Meaning that the total effect of the hedonic value on acceptance is that one additional hedonic word, offers 2.8% more acceptance (β = .028).

- Utilitarian value is also affecting acceptance significantly (p-value = .021) and positively (β = .028). So, one additional utilitarian word offers 0.028 (2.8%) more acceptance. As there is no difference in the effect of hedonic and utilitarian value, hypothesis 2 cannot be confirmed.

- Acceptance affects buying intentions positively (β = .65) and significantly (p-value = <2e-16).

- Finally, it is found that acceptance fully mediates the relations between hedonic product value on buying intentions.

Include hedonic benefits in the product description, or not?

Thanks to this research, we learned how acceptance affects purchasing intentions and how increasing product value makes customers more likely to buy innovation. In order to achieve that, the description of the innovation could focus more on hedonic words, as they affect buying intentions. For example, words describing the innovation could include how the product will provide satisfaction, or how useful it is for the customer. The emphasis should be placed on how will customers enjoy using the new product, as this product value increases the likelihood of a customer purchasing the innovation.

Managers can guide and design marketing strategies, that will navigate towards the hedonic experience when using the innovation, since customers may be more likely to try a new product if they think that it will satisfy them. Hence, the key is to focus on words that promote the pleasure and satisfaction that the customer will experience by using the product. This will also help customers to better understand the benefits of using the innovation thus making it easier for them to make a final decision.

References

Bettiga, D., Bianchi, A. M., Lamberti, L., & Noci, G. (2020). Consumers emotional responses to functional and hedonic products: A neuroscience research. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 559779, 1-13.

Bettiga D., & Lamberti L. (2017). Exploring the adoption process of personal technologies: a cognitive-affective approach. The Journal of High Technology Management Research, 28(2), 179–187.

Castellion, G., & Markham, S. K. (2013). Perspective: New product failure rates & influence of argumentum ad populum and self‐interest. Journal of Product Innovation & Management, 30(5), 976-979.

Dhar, R., & Wertenbroch, K. (2000). Consumer choice between hedonic and utilitarian goods. Journal of Marketing Research, 37(1), 60–71.

Fandos, C., & Flavian, C. (2006). Intrinsic and extrinsic quality attributes, loyalty and buying intention: an analysis for a PDO product. British Food Journal, 108(8), 646-662.

Holbrook M.B., & Hirschman E.C. (1982). The experiential aspects of consumption: consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. Journal of Consumer Research, 9(2), 132–140.

Kivetz R., & Simonson I. (2002). Earning the right to indulge: effort as a determinant of customer preferences toward frequency program rewards. Journal of Marketing Research, 39(2), 155–170.

Lu, J., Liu, Z., & Fang, Z. (2016). Hedonic products for you, utilitarian products for me. Judgment and Decision Making, 11(4), 332–341.

Peppard, J. & Butler, P. (1998). SWP 1 L/98 Consumer Purchasing on the Internet: processes and prospects – cranfield university.

Rogers, E.M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). New York: Free Press.

Rooks, M. (2022). 30 000 different products and counting: The average grocery store, ICSID. Available at: https://www.icsid.org/uncategorized/how-many-products-are-in-a-typical-grocery-store/

Rura-Polley, T. (2001). Innovation: Organizational. In N. J. Smelser & P. B. Baltes (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 7536-7540.

Schneider, J. and Hall, J. (2021). Why most product launches fail, Harvard Business Review, April.

Shiu, J. Y. (2021). Risk-reduction strategies in competitive convenience retail: How brand confusion can impact choice among existing similar alternatives. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 61, 102547.

Singh, S. (2005). Cultural differences in, and influences on, consumers’ propensity to adopt innovations. Emerald Insight.

Voss, K. E., Spangenberg, E. R., & Grohmann, B. (2003). Measuring the hedonic and utilitarian dimensions of consumer attitude. Journal of Marketing Research, 40(3), 310–320.